I know this is too long. However, the case for the Baltic countries to be admitted forthwith to the Eurozone is overwhelming; and the obtuseness of the ECB and the European Commission - not to mention their disdainful arrogance towards these countries - is so staggering, that I hope some of you may read this to the end.

Those EU Member States that already have a fixed exchange rate with the euro (Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Bulgaria) could and should enhance the credibility of their exchange rate arrangement and strengthen nominal convergence by adopting the euro as joint legal tender alongside their national currencies. The national currency would be retained, alongside the euro, as joint legal tender until full membership in the EMU is achieved. This treatment of the euro as a parallel currency with equal ‘rights’ to the domestic currency, is a way to achieve most of the benefits of unilateral euroisation without finding oneself in conflict with the Treaty and Protocol governing formal EMU membership requirements and procedures.

While for the four countries under consideration the key criteria for EMU membership are the inflation criterion and the exchange rate criterion, I shall briefly summarise all nominal convergence criteria.

1. The Maastricht convergence criteria

The convergence criteria for EMU membership (the so-called Maastricht criteria) are as follows:

The fiscal criteria

The fiscal requirement for EMU membership is that at the time of the examination the Member State is not the subject of a Council decision under Article 104(6) of the Treaty that an excessive deficit exists. An excessive deficit exists if either the deficit criterion or the debt criterion are not satisfied:

(1) the deficit criterion: the ratio of the general government financial deficit to GDP cannot exceed the reference value of 3 percent unless either the ratio has declined substantially and continuously and reached a level that comes close to the reference value; or, alternatively, – the excess over the reference value is only exceptional and temporary and the ratio remains close to the reference value;

(2) the debt criterion: the ratio of the stock of gross general government debt to GDP cannot exceed the reference value of 60 percent of annual GDP unless the ratio is sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace.

The interest rate criterion

For a period of one year before the examination, a Member State has had an average nominal long-term interest rate that does not exceed by more than 2 percentage points that of, at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability.

The exchange rate criterion

The Member State must observe the normal fluctuation margins provided for by the exchange-rate mechanism of the European Monetary System (15 percent on either side of a central rate defined with respect to the euro), without severe tensions for at least two years before the examination, without devaluing its currency’s bilateral central rate against the currency of any other Member State on its own initiative.

The inflation criterion

As it was the inflation criterion that has kept Estonia and Lithuania out of the EMU, it is worthwhile to spell it out in detail, and specifically to bring out where the Treaty and the Protocol speak and where the ECB and the Commission are themselves making up criteria, reference values and benchmarks.

The Treaty and Protocol requirements

Article 121 (1), first indent, of the Treaty requires:

“the achievement of a high degree of price stability; this will be apparent from a rate of inflation which is close to that of, at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability”.

Article 1 of the Protocol on the convergence criteria referred to in Article 121 of the Treaty stipulates that:

“the criterion on price stability referred to in the first indent of Article 121 (1) of this Treaty shall mean that a Member State has a price performance that is sustainable and an average rate of inflation, observed over a period of one year before the examination, that does not exceed by more than 1½ percentage points that of, at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability. Inflation shall be measured by means of the consumer price index on a comparable basis, taking into account differences in national definitions.”

The ECB’s and European Commission’s interpretation and operationalisation of the inflation criterion in the Treaty and Protocol

As stated in the Treaty and Protocol, the inflation criterion is non-operational, as it does not explain what is meant by “… the three best performing Members States in terms of price stability”.

It would seem, however, that this ought not to pose a problem, because the ECB, the European institution whose mandate it is to maintain price stability, has, not surprisingly, developed an operational, numerical definition of what is meant by price stability in the euro area. On its website, the ECB states: “The primary objective of the ECB’s monetary policy is to maintain price stability. The ECB aims at inflation rates of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.” It elaborates on this elsewhere on its website as follows:

“While the Treaty clearly establishes the maintenance of price stability as the primary objective of the ECB, it does not give a precise definition of what is meant by price stability.

Quantitative definition of price stability

The ECB’s Governing Council has defined price stability as "a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2%. Price stability is to be maintained over the medium term".

The Governing Council has also clarified that, in the pursuit of price stability, it aims to maintain inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.”

This would seem to carry the logical implication that the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability would be the three Member States whose inflation rates would be closest to but below 2%. The inflation threshold that a Member State wishing to join EMU should not exceed, would therefore be given by 1½ percent plus the average rate of inflation of the three Member States with inflation rates closest to but below 2 percent

Strangely, however, the operational definition of price stability that the ECB uses for itself (that is, for the existing members of the euro area) is not the operational definition the ECB and the Commission impose on Member States wishing to join the EMU. That rate is defined as follows in the ECB’s 2007 Convergence report (ECB (2007)) (similar statements can be found in all earlier Convergence Reports by the ECB and the Commission, e.g. European Monetary Institute (1996; 1998), European Central Bank (2000; 2002; 2004; 2006a,b), European Commission (1998; 2000; 2002; 2004; 2006a,b,c; 2007a,b)).

“…the notion of “at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability”, which is used for the definition of the reference value, has been applied by taking the unweighted arithmetic average of the rate of inflation of the following three EU countries with the lowest inflation rates: Finland (1.3%), Poland (1.5%) and Sweden (1.6%). As a result, the average rate is 1.5% and, adding 1½ percentage points, the reference value is 3.0%.”

To calculate ‘the notion of “at most, the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability”’, the ECB and the Commission therefore take the average of the three lowest (but non-negative) inflation rates among all EU members – those already full members of the EMU, those who are actively trying to meet the EMU membership criteria, and those who are not actively pursuing EMU membership. Not actively pursuing full EMU membership could be legally the case for the two countries with an opt-out, the UK and Denmark. In practice, any country not wishing to join but not in possession of an opt-out, can always choose not to meet one of the criteria for membership. Sweden does this with respect to the exchange rate criterion.

2. ECB and Commission: better consistently wrong than inconsistent but right?

It is clear that it makes no sense to have one concept of price stability for existing Eurozone members (inflation below but close to two percent over the medium term) and a completely different, and in practice much more restrictive, price stability concept for would-be new members (the average of the three lowest inflation rates among all EU Member States, as long as these inflation rates are not negative). Why set a higher standard for candidate members than for existing members?

A further unfortunate feature of the Maastricht inflation criterion, as interpreted by the Commission and the ECB (the Treaty and protocol are rather vague) is that its benchmark is based on the 3 lowest (non-negative) inflation rates among all EU members, (25 at the time of Lithuania’s and Estonia’s unsuccessful first attempts to join the EMU), and not just on the inflation performance of the Eurozone members (12 in number when Lithuania was formally turned down, currently 13 and soon 15, with Cyprus and Malta joining on January 1, 2008). When Lithuania failed the test, two of the three lowest inflation rates used in the calculation of the inflation benchmark were for countries that are in the EU but not in EMU – Poland and Sweden. The inflation rates of countries in the EU but not in the EMU are no more relevant for whether a candidate country should be admitted to the EMU, than would be the inflation rates of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Once can see how and why, historically, these now inane (indeed insane) criteria were put together. What the authors of the Treaty and Protocol were thinking of was the creation ab initio of EMU through the joining in monetary union of a significant number of countries. They wanted not just a monetary union with a common rate of inflation among member states, but one with a common and low rate of inflation. All EU members were expected to be striving actively for EMU membership, so best-performing was naturally measured with respect to the complete set of EU members.

That was then. We now have a functioning EMU with a low EMU-wide rate of inflation. Common sense now calls for the same definition of price stability to be used for candidate members as for the existing EMU members. Actually, as there is only one monetary policy for the entire EMU, even the inflation rates of the individual EMU Member States is irrelevant for the construction of an inflation benchmark. Both the economics and the politics of a monetary union dictate that the benchmark be based on the inflation performance of just the EMU area as a whole.

When one points out to the ECB and the Commission that their inflation criterion and numerical benchmarks make no sense, all they say in reply is, that this is how it was done in the past. Because the ECB and Commission got it wrong before, they are honour-bound to repeat the mistake again today and tomorrow. To do otherwise would violate equity vis-à-vis those who managed to pass the (wrong) tests in the past. The fact that until Lithuania was rejected for membership and Estonia was strongly discouraged from pressing its application, no application for EMU membership had ever been rejected rather undermines the ‘fairness vis-à-vis earlier applicants argument.

For reasons understood only by themselves, the ECB and Commission therefore continue to make these nonsensical demands, even if the Treaty and Protocol do not require it. The Commission and the ECB don’t mind doing things that are illogical, costly and potentially destructive, as long as there is a precedent for it. They would rather be consistently wrong than inconsistent but right.

3. Dirty politics: why is the inflation criterion the only one for which the ECB’s and Commission’s interpretation is rigidly enforced?

In the case of Lithuania and Estonia, the ECB and the Commission have chosen to stick rigidly to their interpretation and quantitative implementation of the inflation criterion, even though this made no economic sense. Strangely enough, the Commission and the ECB have, in the past, forgiven or waved through many clear violations of numerical criteria stated explicitly in the Treaty and the Protocol, rather than just dreamed up by the Commission or the ECB.

To me this suggests either that the ECB’s and Commission’s decision processes as regards the Maastricht criteria being met are deeply political – indeed a dirty game - or that a monumental mistake was made when Lithuania was blackballed and Estonia was pressured into postponing its application for EMU membership.

Forgiving failures to meet the exchange rate criterion

Italy and Finland did not meet the exchange rate criterion for EMU membership. While they had spent 2 years in the exchange-rate mechanism of the European Monetary System when they joined the EMU, they had not observed the normal fluctuation margins provided for by the exchange-rate mechanism of the European Monetary System without severe tensions for at least two years before the examination - as was the requirement of the Treaty. The Commission judged that, by the time of the examination, the currency, despite not having been in the ERM for two years, had displayed sufficient stability for two years. This is a triumph of good sense over the letter of the law and the exact wording of the Treaty and Protocol. Why could this good sense not be called upon when the inflation criterion was being evaluated for Lithuania and Estonia?

Forgiving failures to meet the fiscal criteria

Both Italy and Belgium had debt-to-GDP ratios well above 100 percent when they were admitted to the EMU. While Belgium has consistently reduced its debt ratio since then, Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio even today is above 100 percent. Allowing it into the EMU violated both the spirit and the letter of the Treaty and Protocol.

Germany did not meet the debt criterion for EMU membership at the time of the examination and should not have been admitted. In 1998 its debt-to-GDP ratio was 60.9 percent and in 1999 it was 61.2 percent. So it was above 60 percent and rising! Despite some attempts to get serious about its public debt, even in 2006 the German debt to GDP ratio still was 67.9 percent.

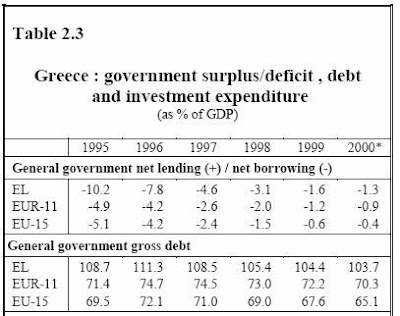

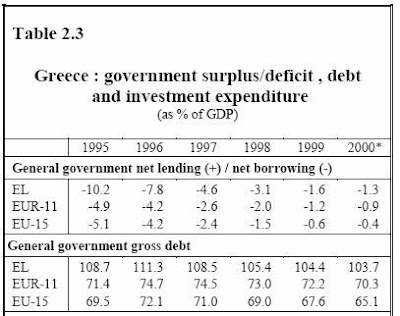

The most extreme example of a country not meeting the Maastricht fiscal criteria and yet becoming an EMU member is Greece. Greece did not, by any stretch of the imagination, meet the debt criterion for EMU membership. In addition, the Greek authorities fiddled the data for the calculation of the general government deficit. Until this cheating was discovered, it appeared Greece had met the deficit criterion (general government deficit less than 3 percent of GDP), as is clear from Table 2.3 below (Table 2.3 and Table 2.5, including the Table numbers, are taken from the Convergence Report 2000 of the ECB). The convergence programme for Greece when it was admitted to EMU is included as Table 2.5 below, as a reminder of just how out of touch with reality the ECB and European Commission were when they admitted Greece into the EMU.

When the statistical cheating was discovered and the deficit data were revised upwards, it was clear that both on the deficit and the debt criterion, Greece would have failed to qualify for EMU membership starting January 2001. The debt ratios remain above 100 percent of annual GDP even today.

Rather than suspending Greece’s membership in the EMU after the discovery of the irregularities in its qualification for admission, and requiring it to qualify again (which would have required at least a two-year transition period) Greece was allowed to continue as a full member without any sanctions. The integrity of the vetting process for the Maastricht criteria was further compromised through this. The message is clear: “do anything necessary to formally meet the criteria at the time”. Cheat if necessary. If you are found out after you are allowed in as a member, nothing will happen to you.”

Recently, the Greek government has discovered that there is a second way of lowering a ratio that is uncomfortably high: if reducing the numerator is not practicable, then increasing the denominator may be an option. Eurostat are currently reviewing the merits of the Greek statistical authorities’ request for a significant increase in measured GDP, reflecting, according to the Greek authorities, the informal sector and other unrecorded economic activity.

4. The problem: the inflation criterion for countries with a fixed exchange rate with the euro

Countries that have a fixed exchange rate with the euro face special problems meeting the inflation criterion for EMU membership. The inflation criterion makes no sense from an economic perspective for countries wishing to join an already existing monetary union when that monetary union has a price stability objective, operationally expressed as a target for inflation in the medium term. The first-best solution would be for all countries wishing to join the EMU and meeting the fiscal, interest rate and exchange rate criteria to be allowed to do so. This is the only solution that makes sense. However, politics and logic are not often encountered in the same space.

Candidate EMU members on a fixed exchange rate with the euro have to deal with the problem that their efficient, optimal rate of equilibrium inflation may well be higher than the existing EMU average. That is because of the Balassa-Samuelson effect. When transition countries with a lower level of productivity and per capita income than the existing EMU average succeed in converging gradually but effectively to the higher levels of productivity and per capita income of the EMU, productivity in the traded goods sectors typically catches up faster than productivity in the non-traded good sectors. The result is that transition countries achieving successful real convergence will experience an appreciation of their real exchange rates. With a fixed nominal exchange rate, real appreciation means higher inflation in the candidate EMU members than in the EMU.

What are the solutions?

One solution would be to abandon the fixed exchange rate regime (the currency board), float the currency and allow it to appreciate in nominal terms for at least a year to get inflation down to the benchmark level. Once that has been achieved, the exchange rate gets locked in irrevocably. I hope that not even the ECB and the Commission recommend such an extraordinary policy sequence. You have the closest thing to a common currency (a currency board); you have to abandon this currency board to float the exchange rate for a year or longer to meet the inflation criterion; if you succeed you get rewarded by going back to where you started from. This would be insane.

Another solution is to create a reduction in the output gap of sufficient depth and duration to bring down the inflation rate to the level of the inflation benchmark. Fiscal policy or credit controls could be used to reduce the domestic output gap and lower inflation. Unless the economy is overheating (that is, unless in addition to the Balassa-Samuelson inflation premium there is also a cyclical inflation premium), contracting demand would mean deliberately creating a recession: a pointless sacrifice of output and employment. It should be rejected. 5. A partial solution: make the euro joint legal tender with the national currency

One way for an EU member wishing to become a full EMU member to give visible expression to its desire for and commitment to eventual full EMU participation, is for it declare the euro to be joint legal tender for all transactions under the country’s jurisdiction, on the same terms as the national currency. This would also allow the country to achieve effectively all of the benefits of full monetary union, with the exception of (1) a share in the ECB’s seigniorage (profits), (2) access to the ECB/ESCB as lender of last resort, and (3) a seat on the ECB Governing Council (further development and discussion of this proposal can be found in Bratkowski and Rostowski (2002), Schoors (2002), Buiter and Grafe (2002), Buiter (2005) and Buiter and Sibert (2006a,b)).

Legal tender, also called forced tender, is payment that, by law, cannot be refused in settlement of a debt denominated in the same currency. Currently, in Estonia, only the Estonian kroon is legal tender. This is clear from the Currency Law of the Republic of Estonia, some key clauses of which are reproduced below in Box 1. An important part of legal tender status is that taxes and fines payable to the state can be paid in legal tender, and that indeed the state can require this.

Box 1

Extracts from the Currency Law of the Republic of Estonia

Clause 3. Legal tender

The sole legal tender in the Republic of Estonia is Estonian kroon. The legal persons and single individuals located in the Republic of Estonia have no right to use any other legal tender except Estonian kroon in the accountancy between them.

Clause 4. Obligation to accept the legal tender of the Republic of Estonia without restrictions

Eesti Pank, as well as all other banks and credit institutions of the Republic of Estonia are obliged to accept the legal tender of the Republic of Estonia without restrictions. Other legal persons are obliged to accept valid coins up to the amount of 20 Estonian kroons at a time, but banknotes without any restrictions.

Clause 5. Exchangeability of Estonian kroon with other currencies

The exchangeability of Estonian kroon with other currencies will be determined by law. The conditions and procedure of exchanging Eesti kroon into foreign currencies will be determined by Eesti Pank.

Clause 71 Refusal to accept legal tender

(1) Refusal to accept legal tender upon sale of or payment for goods or services is punishable by a fine of up to 200 fine units.

(2) The same act, if committed by a legal person, is punishable by a fine of up to 30,000 kroons.

Legally, all that is required to make the Estonian Kroon and the euro joint legal tender in Estonia, is the rewriting the Currency Law of the Republic of Estonia along the lines suggested in Box 2.

Box 2

Proposal for a revised

CURRENCY LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA

Clause 1. Monetary unit

The monetary units of the Republic of Estonia are the Estonian kroon, which is divided into one hundred cents, and the euro, which is divided into one hundred cents. The cash of the Republic of Estonia is in circulation in the form of banknotes and coins.

Clause 2. Issuing Estonian kroon

The sole right to issue and to remove from circulation the Estonian kroon belongs to Eesti Pank. Eesti Pank determines the denominations of the banknotes and coins as well as their design.

Clause 3. Legal tender

The sole legal tender in the Republic of Estonia are the Estonian kroon and the euro. The legal persons and single individuals located in the Republic of Estonia have no right to use any other legal tender except the Estonian kroon or the euro in the accountancy between them.

Clause 4. Obligation to accept the legal tender of the Republic of Estonia without restrictions

Eesti Pank, as well as all other banks and credit institutions of the Republic of Estonia are obliged to accept the legal tender of the Republic of Estonia without restrictions. Other legal persons are obliged to accept valid coins up to the amount of 20 Estonian kroons at a time or up to the amount of 1.28 euros at a time, but banknotes without any restrictions.

Clause 5. Exchangeability of Estonian kroon with other currencies

The exchangeability of Estonian kroon with other currencies will be determined by law. The conditions and procedure of exchanging Eesti kroon into foreign currencies will be determined by Eesti Pank.

Clause 6. Damaged and spoilt currency

Damaged and spoilt banknotes and coins of the Republic of Estonia will be received and replaced by Eesti Pank and banks authorized by it, in condition that at least half of the banknote is preserved and the serial number is fully legible; on a coin, at least the denomination and time of minting must be legible.

Other legal persons are not obliged to accept damaged and spoilt banknotes and coins.

Clause 7 Refusal to accept legal tender

(1) Refusal to accept legal tender upon sale of or payment for goods or services is punishable by a fine of up to 200 fine units.

(2) The same act, if committed by a legal person, is punishable by a fine of up to 30,000 kroons or 1,917.35 euros.

(3) The provisions of the General Part of the Penal Code (RT I 2001, 61, 364) and of the Code of Misdemeanour Procedure (RT I 2002, 50, 313) apply to the misdemeanours provided for in this section.

(4) Extra-judicial proceedings concerning the misdemeanours provided for in this section shall be conducted by:

1) the Consumer Protection Board;

2) police prefecture.

In principle, a variety of monetary and exchange rate regimes are consistent with having the euro as a parallel currency and joint legal tender. This includes managed and freely floating exchange rate regimes. A fixed exchange rate regime with the euro, and especially a currency board is, however, the natural vehicle for the euro as joint legal tender. It is also a natural waiting room for the eventual full EMU membership.

Some further refinements

The exchange rate of the Estonian kroon and the euro is 15.64664 Estonian krooni for one euro. That is not a very convenient number. It would make sense to have a currency reform that creates a new Estonian kroon (perhaps called the Estonian eurokroon, or eurokroon for short, whose value is 15.64664 old Estonian krooni. One new Estonian eurokroon would therefore equal one euro - nice and simple.

It would also make sense to make the coins and currency notes of the new Estonian eurokroon sufficiently similar in shape, weight and appearance (without, however, risking accusations of counterfeiting!) that all new vending machines and other electro-mechanical, digital and optical instruments that handle coins and notes can use both euros and eurokrooni interchangeably.

Formally, the exchange rate regime would remain a currency board. In the strict version of a currency board, the entire domestic base money stock (coin and currency and banks’ balances with the central bank) must be backed by international reserves (euros in practice). It would therefore make sense, since there is no opportunity cost involved in replacing domestic coin and currency with euros, to gradually reduce the issuance of krooni coin and currency. Effective complete euroisation of cash could take place without the formal abolition of the domestic currency. The eurokroon would continue to exist, as a numeraire, means of payment/medium of exchange, store of value and legal tender alongside the euro, but you just would not see very many of them.

By encouraging de facto euroisation, that is, the increased use of the euro as the unit of account in contracts (including financial contracts and instruments) and for pricing, as the medium of exchange/means of payment and as store of value, the risk associated with the status of being almost-but-not-quite in the EMU would be much reduced. Exchange rate risk (as regards the exchange rate of the domestic currency vis-à-vis the euro) would cease to be a concern as fewer and fewer contracts and financial instruments are denominated in domestic currency. To avoid giving ammunition to the forces of darkness in Brussels and Frankfurt, however, it is essential that establishing the euro as joint legal tender is not formally and legally the unilateral adoption of the euro as the only legal tender, and the abolition of the domestic currency.

6. The euro as joint legal tender is not unilateral euroisation and is consistent with the provisions and requirements of the Treaty and Protocol for full EMU membership

According to the letter of the Treaty, unilateral euroisation, is not compatible with the Maastricht criteria if it involves the unilateral abolition of the national currency. The argument is that, once the national currency has been abolished, there no longer is any way for the Council of Ministers to determine the irrevocably fixed conversion rate at which the candidate EMU member’s currency eventually joins EMU. The candidate EMU member would have been able to determine its irrevocably fixed euro conversion rate unilaterally. That would be a bridge too far. The ECB and the Commission will have to cross that bridge if and when Montenegro, which has the euro as its sole legal tender today, prior to EU membership, joins the EU and the EMU, but it is too early to speculate about how that conundrum will be resolved.

In addition to Montenegro, the euro plays a key role in the domestic monetary arrangements of a number of small European countries, none of which are formally members of the EU. The euro is legal tender in Monaco, San Marino and Vatican City, which are licensed to issue and use the euro. Like Montenegro, Andorra has the euro as legal tender but is not licensed to issue any euro coins or notes. The same holds for the sub-national entity Kosovo.

There are also some obvious parallels with the pre-Euro Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union (1922-2002); from 1944, the Belgian franck was joint legal tender in Luxembourg with the Luxembourg franc, and the Luxembourg franc was joint legal tender in Belgium with the Belgian franc (although you would not have thought so, if you tried to pay with Luxembourg francs in Brussels!)

The ECB’s position on the issue is the following “Any unilateral adoption of the single currency by means of “euroisation” outside the Treaty framework would run counter to the economic reasoning underlying Economic and Monetary Union, which foresees the eventual adoption of the euro as the end-point of a structured convergence process within a multilateral framework. Unilateral “euroisation” cannot therefore be a way of circumventing the stages foreseen by the Treaty for the adoption of the euro” (European Central Bank (2003)).

This argument is correct only if unilateral euroisation means the unilateral abolition of the domestic currency and its replacement by the euro. Having the euro as a parallel currency and joint legal tender without abolishing the domestic currency, and leaving the Council of Ministers the opportunity to determined the eventual irrevocably fixed conversion rate between the domestic currency and the euro, is quite consistent with the Treaty and Protocol. There is no circumventing of the stages foreseen by the Treaty for the adoption of the euro. The structured convergence process is not encumbered or undermined in any way.

7. What the euro as joint legal tender does not achieve

Adopting the euro as joint legal tender does not achieve three things:

- A seat on the Governing Council of the ECB;

- A share of the seigniorage (profits) of the ECB;

- Access to ECB/ESCB resources by domestic banks for lender of last resort operations.

These continuing lacunae are, of course, the same ones experienced by the would-be euro area members under their current currency board arrangements. They are ‘deficiencies’ only when compared to a situation of full membership in the EMU. Since there is no reason why adopting the euro as joint legal tender would delay full membership in the EMU, the opportunity cost of doing so is really zero.

8. Safety in numbers

The ECB and the European Commission are unlikely to welcome with open arms the adoption of the euro as joint legal tender. It is my view that there is not much they can do about it. Still, there is safety in numbers. If, say, all four currency board countries in the EU, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Bulgaria, were to take the identical action simultaneously, the odds on even token attempts to interfere with this decision by Brussels or Frankfurt would be negligible.

I also believe that while the official response may be frosty, at best, there is a lot of sympathy for the Baltic countries and a lot of covert support for their ambition to adopt the euro as soon as possible. It is quite likely that the failure of Lithuania and Estonia to become full members in 2007 was just the result of a big error of judgement in Brussels.

I share the view of many observers that those in charge of the EMU convergence assessment in Brussels believed that Lithuania and Estonia would be willing to cheat to achieve membership. The candidate EMU members could have done this by fiddling with VAT or other indirect taxes and by messing with utility tariffs – that’s what Slovenia did, after all, and Slovenia was rewarded for it with EMU membership. They could even have followed the Greek example and simply have doctored the price data. Finally, the great and the good in Brussels and the national capitals probably did not believe it possible that the ECB would produce quite the eruption of self-righteousness and stupidity that it did by denying Lithuania EMU membership when its inflation rate exceeded the benchmark rate by barely one tenth of one percent. There may be a lot of sympathy in Brussels and in many of the EU capitals , and even some surreptitious support for the adoption of the euro as joint legal tender by the currency board countries of Central Europe and the Baltics.

The very creation of EMU was a triumph of political will over technocratic timidity. Distinguished economists (quite a few of them, like Martin Feldstein, from the USA) said it could never happen, and if it happened it would collapse in short order. Perhaps history will repeat itself. Ultimately it is the politicians in the Council of Ministers rather than the technocrats in Frankfurt and Brussels who determine whether a country will be allowed to join the EMU (the ECB and the Commission have only an advisory function). It is therefore possible that a country that starts of by adopting the euro as joint legal tender, may end up with full euroization, not through unilateral euroisation but through consensual euroisation with the blessing of the Council of Ministers. But it is time to press on with joint legal tender regardless.

Conclusion

The frightening financial turmoil of the past few months has provide a stark reminder of the truth that small open economies with unrestricted financial capital mobility have only one sensible monetary option: to join the nearest big currency area/monetary union. This is true not just in Europe. New Zealand is a model of monetary and fiscal rectitude and of deep structural reform. Yet it is a rudderless plaything of the international capital markets. It cannot control its exchange rate. It has to do incredible things to its monetary policy interest rate to keep any kind of control over domestic inflation. It is not surprising that monetary union with Australia is being talked about in responsible policy circles as an option.

For Estonia and the other currency board countries, the earliest possible full membership of EMU is the dominant policy option. To minimize the risk of monetary and financial instability in the period until full membership is achieved, adoption of the euro as joint legal tender is a sensible transitional option. It will not delay the EMU membership process, but it will make the transition less hazardous.

References

Bratkowski, A. and Rostowski, J. (2002), ‘Why Unilateral Euroization Makes Sense for (some) Applicant Countries,’ in Beyond Transition eds. M. Dabrowski, J. Neneman and B. Slay, Ashgate Buiter, Willem H. (2005) "To Purgatory and Beyond; When and how should the accession countries from Central and Eastern Europe become full members of the EMU?". In Fritz Breuss and Eduard Hochreiter (eds.) Challenges for Central Banks in an Enlarged EMU, Springer Wien New York, pp. 145-186.

Buiter, Willem H. and Clemens Grafe (2002), "Anchor, Float or Abandon Ship: Exchange Rate Regimes for the Accession Countries", in Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review, No. 221, June 2002, pp. 1-32.

Buiter, Willem H. and Anne C. Sibert (2006a), "Eurozone Entry of New EU Member States from Central Europe: Should They? Could They?", in Development & Transition, UNDP-LSE Newsletter, 4, June, pp. 16 -19.

Buiter, Willem H. and Anne C. Sibert (2006b), "When Should the New Central European Members Join the Eurozone?", Bankni vestnik - The Journal for Money and Banking of the Bank Association of Slovenia, Special Issue, Small Economies in the euro area: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities, 11/2006, pp. 5-11.

Égert, Balázs, Imed Drine, Kirsten Lommatzsch and Christophe Rault (2003), “The Balassa-

Samuelson Effect in Central and Eastern Europe: Myth or Reality? Journal of Comparative

Economics, vol 31, pp 552–572, in September, 2003.

European Commission (1998), “Convergence Report 1998”,

European Economy, No 65. 1998. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg. 411pp. Tabl. Graph. Bibliogr.. CM-AR-98-001-EN-C; ISSN0379-0991.ISSN 0379-0991 http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/1998/ee65_98en.pdf

European Commission (2000), “Convergence Report 2000”,

European Economy, No 70. 2000. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg. 393pp. Tabl. Graph. Bibliogr.) KC-AR-00-001-EN-C; ISBN 92-828-9708-7; ISSN0379-0991

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/

convergencereports_en.htm

European Commission (2002), 2002 Convergence Report on Sweden, http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/

convergence/report2002_en.htm

European Commission (2004), “Convergence Report 2004”, European Economy, Special Report 2/2004. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/2004/cr2004_en.pdf

European Commission (2006a), “2006 Convergence Report on Slovenia”, European Economy, Special Report. No. 2. 2006. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg. 104pp. Tables, Graphs, Bibliog.)

KC-AF-06-002-EN-C; ISBN 92-79-01218-5; ISSN 1684-033X.

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/2006/eesp206en.pdf

European Commission (2006b), “2006 Convergence Report on Lithuania”, European Economy, Special Report. No. 2. 2006. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg. 104pp. Tables, Graphs, Bibliog.)

KC-AF-06-002-EN-C; ISBN 92-79-01218-5; ISSN 1684-033X.

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/2006/eesp206en.pdf

European Commission (2006c) “2006 Convergence report”. European Economy No. 1. 2006. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg. 184pp. Tables, Graphs, Bibliog.,

KC-AR-06-001-EN-C; ISBN 92-79-01202-9; ISSN 0379-0991., http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/2006/ee106en.pdf

European Commission (2007a), “2007 Convergence report on Malta”, European Economy,. No. 6/2007. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg.

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/2007/ee0607_en.pdf

European Commission (2007b), “2007 Convergence report on Cyprus”, European Economy. No. 6/2007. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg.)

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy

/2007/ee0607_en.pdf

European Central Bank (2000), Convergence Report 2000, May, Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 92-9181-061-4 http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr2000en.pdf

European Central Bank (2002), Convergence Report 2002, May, Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 92-9181-282-X, http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr2002en.pdf

European Central Bank (2004), Convergence Report 2004, May, Frankfurt am Main, November, ISSN 1725-9312 (print), ISSN 1725-9525 (online),

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr2004en.pdf

European Central Bank (2006a), Convergence Report May 2006, Frankfurt am Main, May, ISSN 1725-9312 (print), ISSN 1725-9525 (online)

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr2006en.pdf

European Central Bank (2006b), Convergence Report December 2006, Frankfurt am Main, December, ISSN 1725-9312 (print); ISSN 1725-9525 (online),

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr200612en.pdf

European Central Bank (2007), Convergence Report May 2007, Frankfurt am Main, May, ISSN 1725-9312 (print), ISSN 1725-9525 (online),

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr200705en.pdf

European Monetary Institute (1996), Progress towards convergence, November. Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 92-9166-011-6,

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr1996en.pdf

European Monetary Institute (1998), Convergence Report; Report required by Article 109 j of the Treaty establishing the European Community, March, Frankfurt am Main, ISBN 92-9166-057-4, http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/conrep/cr1998en.pdf

Schoors, Koen (2002), “Should the Central and Eastern European Accession Countries

Adopt the Euro before or after Accession?” Economics of Planning, Springer, vol. 35(1), pages 47-77.

Italy and Finland joined EMU at its start, on January 1, 1999, even though at the time the decision to admit these two countries was made, they had not yet spent two years in the ERM. This tension is clearly reflected in the language used in the Commission’s Convergence Report. “Although the lira has participated in the ERM only since November 1996, it has not experienced severe tensions during the review period and has thus, in the view of the Commission, displayed sufficient stability in the last two years.” (European Commission (1998, p24). This assessment was made, that is, the examination took place, in March 1998.